This is an exquisite cake: feather light and springy as a pillow, fragrant with good citrus, extra virgin olive oil, and dessert wine. Developed at Chez Panisse in the 1980s where it was made with Sauternes, this cake is subtle, complex and unexpected: as sweet as you could wish in a cake, but not with a cake’s usual sugar sweetness. It has the magic of alchemy, no single note dominating. It’s a recipe for your best eggs and olive oil, for an orange and lemon that smell and taste of the sun, and a dessert wine you would buy for an occasion — not one to break the bank, but one you enjoy drinking (as there’s the rest of the bottle to finish with the cake).

This is an exquisite cake: feather light and springy as a pillow, fragrant with good citrus, extra virgin olive oil, and dessert wine. Developed at Chez Panisse in the 1980s where it was made with Sauternes, this cake is subtle, complex and unexpected: as sweet as you could wish in a cake, but not with a cake’s usual sugar sweetness. It has the magic of alchemy, no single note dominating. It’s a recipe for your best eggs and olive oil, for an orange and lemon that smell and taste of the sun, and a dessert wine you would buy for an occasion — not one to break the bank, but one you enjoy drinking (as there’s the rest of the bottle to finish with the cake).

Using such special ingredients makes this cake an offering of note, and those who taste it pay attention. Double-takes are common. Conversation stops. A Norwegian friend of ours could eat two-thirds of it in an evening, going back again and again for another little slice (I really like this cake he would say every time with a shake of the head that meant I can’t help myself ) — and it slices so cleanly it’s all too easy to keep at it.

I love making this cake when friends come for the weekend since it’s so differently delicious, and so easy to eat without spoiling appetites for the catering to come. It’s much requested for birthday celebrations, too, sometimes with vanilla gelato, sometimes with a sabayon made with the same wine used for the cake, sometimes with citrus compote or a lovely peach — but usually without anything else because it’s so fine on its own. It makes a perfect picnic cake, too, no messy buttercream in sight. I have a sweet memory of baking one for my youngest sister, Kitty, more years ago than I can credit, to grace a birthday hike in the golden foothills of northern California. I carried it in my backpack wrapped in a cloth we sat on later to eat, and eat we did: the whole cloud-like cake on that blue-sky day.

I love making this cake when friends come for the weekend since it’s so differently delicious, and so easy to eat without spoiling appetites for the catering to come. It’s much requested for birthday celebrations, too, sometimes with vanilla gelato, sometimes with a sabayon made with the same wine used for the cake, sometimes with citrus compote or a lovely peach — but usually without anything else because it’s so fine on its own. It makes a perfect picnic cake, too, no messy buttercream in sight. I have a sweet memory of baking one for my youngest sister, Kitty, more years ago than I can credit, to grace a birthday hike in the golden foothills of northern California. I carried it in my backpack wrapped in a cloth we sat on later to eat, and eat we did: the whole cloud-like cake on that blue-sky day.

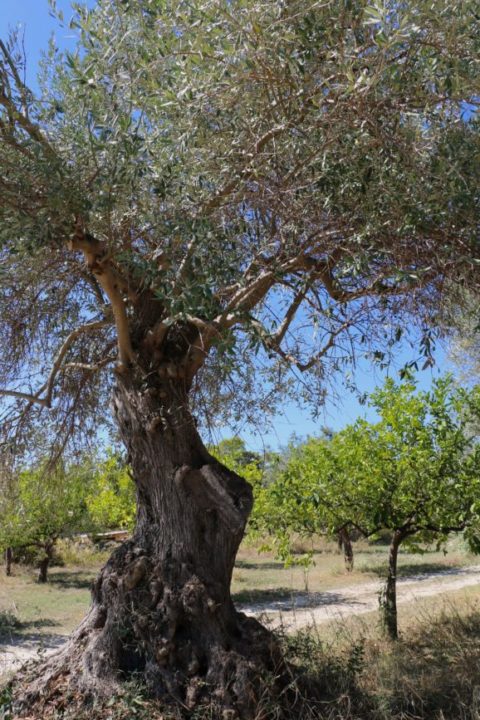

For me it’s a love poem to whomever I bake it for, and to the landscape: the vineyards, olive and citrus groves that make it possible and so special. Those landscapes can be French if I use Sauternes or my usual choice, the good-value Monbazillac — or they can be Sicilian if I use a Passito di Noto or the Malvasia of the Aeolian Islands. Every wine will lend its own character to the cake, and so will every olive oil.

This year I’ll be making it with the beautiful olive oil from Fabio and Annarella’s trees outside Noto in Sicily, which they tend, along with groves of citrus and almonds, on the small organic farm that belonged to Fabio’s grandparents and their grandparents in turn.

This year I’ll be making it with the beautiful olive oil from Fabio and Annarella’s trees outside Noto in Sicily, which they tend, along with groves of citrus and almonds, on the small organic farm that belonged to Fabio’s grandparents and their grandparents in turn.

Our share of this year’s olive oil has just arrived in the post, days after it was pressed: three and a half glorious litres from the trees we admired last October just as the olives were about to be harvested. We fell in love with the taste of the farm’s oil used in the feast Annarella cooked for us on our visit, so were delighted to learn we could have a supply delivered to us in England by taking out a share in the year’s harvest and symbolically adopting a tree. This “adopt-an-olive-tree” arrangement is, like all the best things in life, a mutually beneficial partnership. It helps a young couple with their cash flow so they can keep doing their worthwhile work, and brings us the superb oil that will be a mainstay in our kitchen and remind us of Zisolhouse farm and the Sicilian sun every time we use it.

When we visited this tranquil farm in the countryside just 10 minutes outside Noto city, Fabio showed us the olive, almond and citrus groves it took him five years to reclaim from a thicket of bramble after the farm had fallen into neglect with the passing of the generation who had last worked it. Rather than grubbing up the old tangle and starting again, he and Annarella pruned the trees back into health, grafting new vigour onto the ancient rootstock.

When we visited this tranquil farm in the countryside just 10 minutes outside Noto city, Fabio showed us the olive, almond and citrus groves it took him five years to reclaim from a thicket of bramble after the farm had fallen into neglect with the passing of the generation who had last worked it. Rather than grubbing up the old tangle and starting again, he and Annarella pruned the trees back into health, grafting new vigour onto the ancient rootstock.

The pair are determined to renew the farm in a sustainable way that will preserve it over the long term and contribute to the wider knowledge that will help Sicilian growers, and those elsewhere, to survive the uncertainties of climate change and other pressures. They are unusual even among smaller organic operations in cultivating trees without irrigation, testing the limits as longer dry seasons put ever more pressure on the island’s water supplies. So far the crops are performing well, and the mixed planting also helps to guard against pests and diseases. Fabio has faith in his ancient trees and their ability to keep adapting.

He’s experimented in this way with his citrus as well, grafting sweet varieties onto the robust native wild oranges with their vicious thorns, which have survived many a drought throughout time. He’s also left some wild orange to produce their own flowers, and these have proved to be another crop of value. Their flamboyant blossom are harvested to distil into a preciously small, but powerful, amount of essential oil used in expensive Neroli scents. Fabio learned from an old neighbour to shake the flowers from the branches using upturned umbrellas to catch the flowers as they fall: a sight I would dearly love to witness some day. Imagine the fragrance that must fill the air. It must be some compensation for weary arms.

He’s experimented in this way with his citrus as well, grafting sweet varieties onto the robust native wild oranges with their vicious thorns, which have survived many a drought throughout time. He’s also left some wild orange to produce their own flowers, and these have proved to be another crop of value. Their flamboyant blossom are harvested to distil into a preciously small, but powerful, amount of essential oil used in expensive Neroli scents. Fabio learned from an old neighbour to shake the flowers from the branches using upturned umbrellas to catch the flowers as they fall: a sight I would dearly love to witness some day. Imagine the fragrance that must fill the air. It must be some compensation for weary arms.

But back to our perfumed cake…. Fabio sent three beautiful lemons in the box with our olive oil, and so I am honouring one of them, too, with this cake (the other two are for the lemon pasta that Annarella showed us how to make). The handsome orange I procured from our local shop looks a good one — oranges are at their irresistible peak right now, too — so I’m excited to see how this first cake with our adopted olive oil turns out.

But back to our perfumed cake…. Fabio sent three beautiful lemons in the box with our olive oil, and so I am honouring one of them, too, with this cake (the other two are for the lemon pasta that Annarella showed us how to make). The handsome orange I procured from our local shop looks a good one — oranges are at their irresistible peak right now, too — so I’m excited to see how this first cake with our adopted olive oil turns out.

When you are lucky enough to have such special ingredients with so much heart, you really want to do them justice, and this beautiful cake does. If there is one cake recipe on this blog I hope people will bake and love as their own, it’s this one. It’s probably the single cake I would want with me forever if I could have just one, not only for its sublime flavour and ethereal lightness, but for its associations with sunshine, and the way it does seem to generate the kind of uncomplicated happiness that seems easy on a day spent with the sun. This cake’s honest yet elegant simplicity puts it in a class of its own, and I hope you too will love every wrinkle and golden crumb.

RECIPE

Olive oil and sweet wine cake

Enough for 8-10 slices (and maybe that many people)

Adapted from the Chez Panisse recipe for olive oil and Sauternes cake, first developed by Linda Guenzel and published in The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook (1982), with later adaptations by Lindsay Remolif Shere, as published in her Chez Panisse Desserts (1985). See the notes at the end of the recipe for a comparison of the two.

Tips for choosing ingredients

I have sometimes made this cake with Sauternes, but my usual choice of wine is Monbazillac, as it’s reliably good and a good-value dessert wine with the right amount of sweetness for this cake. I have also used two Sicilian sweet wines — a Passito di Noto, and a Malvasia. Use whatever dessert wine you like as long as it’s comparably sweet. I’ve found that slightly less-sweet wines (such as Essensia, or even a Bristol cream sherry) haven’t been sweet enough. As for the olive oil, use an extra virgin oil whose taste you like. For the citrus zest, use unwaxed (lemons are readily available unwaxed, and you can often find organic unwaxed oranges in the season). Pastry flour (or cake flour) makes for a lighter cake.

Baking tips

You will need a 23cm (9-inch) round cake tin with a removeable bottom, that’s at least 7cm (2¾ inches) deep. A standing-mixer fitted with a whisk attachment is ideal for beating the egg yolks and egg whites.

This cake is exceptionally light and spongy, and therefore tends to fall a little on cooling. You may find, as I do, that the sides wrinkle even when baked and cooled as directed. This doesn’t make any difference to the flavour or texture, so long as the cake is properly baked through.

This cake goes through three controlled temperature changes. The oven starts higher to get the initial lift underway. It’s then lowered partway through so the cake bakes evenly to the centre without overbaking on the outside. Finally, you need to leave it in the oven with the heat turned off (its top covered with a circle of buttered baking-parchment) for about ten minutes longer to finish in the residual heat. This more gradual temperature change also helps minimise shrinkage on cooling.

Try not to open the oven more than you need to, and make sure the cake is fully baked through, as otherwise you can end up with a heavier bottom-inch or so of cake — not what it should be. Test the cake just before turning the oven off, prior to leaving it for the final few minutes in the residual heat. Full instructions on what to look for are included in the recipe.

Ingredients

- 5 large eggs, separated, plus 2 large egg whites

- 150g caster sugar (¾ cup), divided into two equal parts of 75g (6 level tablespoons)

- 1 tablespoon mixed lemon and orange zest from unwaxed fruits, finely grated

- 130g ’00’ fine pastry flour, sifted (or 1 level cup cake flour, sifted before measuring)

- ¼ level teaspoon pouring salt

- 110ml (1/3 cup plus 2 tablespoons) extra virgin olive oil

- 120ml (½ cup) sweet dessert wine like Sauternes or Monbazillac (see ‘Tips for choosing ingredients’, above)

- Optional: ½ teaspoon cream of tartar for beating the egg whites (see notes at the bottom on comparing the two Chez Panisse recipes)

- Optional: a dusting of icing sugar to serve

Directions

- Heat the oven to 190C/375F and position a rack in the middle of the oven with plenty of space above.

- Butter and flour the cake tin (or butter and flour the sides, and line the bottom with a circle of baking parchment); the flour on the sides helps the cake to rise and retain its volume. Make another circle of parchment paper to cover the top of the cake in its final few minutes of baking; butter this on one side, and set aside.

- In a large mixing bowl, whisk the yolks with one-half of the sugar for about 3 minutes or until fairy thick and foamy, and lighter in colour, but not stiff. Swap to a silicone spatula or a spoon, and stir in the mixed citrus zests.

- Working with a hand-held whisk or spatula, mix in the olive oil, and then the wine, scraping the sides and bottom of the bowl as you go.

- Gradually add the flour and salt, and mix gently until the flour has disappeared, but don’t over-work it (a hand-held whisk and/or silicone spatula is ideal for this). Again, scrape the sides and bottom of the bowl to get a smooth mix.

- In a clean large bowl, using clean beaters, whisk the egg whites (with the cream of tartar, if using) at medium speed until they begin to turn white and grow in volume, and then gradually add the remaining sugar and increase the speed. Continue to beat almost to the stiff peak stage, where the whites are thick and shiny, and keep their shape on the beaters, but are not so stiff that they look dry.

- Fold the beaten whites into the batter in three goes, until everything is well-incorporated, being as careful as you can not to deflate the mixture.

- Carefully pour the airy batter into the prepared cake pan, and level the top with a spatula to ensure the sides are even with the middle.

- Bake for an initial 10 minutes at 190C/375F, and then, without opening the oven, reduce the heat to 165C/325F and bake for another 15 minutes. When the cake has been baking for 25 minutes, quickly open the oven and rotate the tin to encourage even baking, and bake for 25 minutes longer — for a total of 50 minutes — or until the cake has risen high in the pan and looks golden brown and set on top.

- Quickly open the oven and test the cake for doneness. It should not be at all hard on the surface, but the centre should feel firm and spring back when lightly pressed (you should not hear any little hiss of air bubbles as you press the centre). The sides should be just coming away from the sides of the pan; and a cake-tester or skewer inserted into the centre should go in without resistance all the way to the bottom, and come out clean of crumbs. If it hasn’t reached this stage, keep the oven on and give the cake another 3-5 minutes and check again. If it has, cover the top with the reserved circle of baking-parchment (buttered side against the cake), turn off the oven, and leave the cake in the oven for a final 10 minutes (for a total of 60 minutes altogether). If you have any concerns that the cake needs a little longer, leave it for 15 minutes in the cooling oven. Or if you think it’s in danger of over-baking in the final 10 minutes, leave the oven-door slightly ajar.

- Set the cake, still in its tin, on a cooling rack out of any draughts, and let it come to room temperature.

- Release the cake from the tin, remove the parchment paper from the bottom if you’ve used it, and place the cake onto a serving platter. Dust with icing sugar if you wish. Store the cake in an airtight container. It will last well for three or four days, but is lightest and loveliest within the first day or two.

- This is excellent on its own, with a small glass of the sweet wine you used in the cake, or with coffee or tea. It is also wonderful with vanilla gelato, a bit of fresh fruit with crème fraiche, or a sabayon made with the wine.

Note for recipe geeks on comparing the two Chez Panisse recipes:

Both recipes produce a gorgeous cake. The differences between them are subtle, but I’ve made the cake so many times I’ve come to have my own preferences and take a bit from both. As with any recipe, some leeway is needed for differences in ovens and cooks themselves, so I’ll do my best to explain the differences between the two Chez Panisse recipes and what changes I’ve made in my interpretation as offered above on this blog.

Pans and pan size: Both original recipes call for a 20-cm (8-inch) cake tin, but I have found again and again that the 23cm (9-inch) pan is better, and the baking times specified in the original recipes work better for this size as well. I have also used a deep angel-food pan to bake this cake, and it works very well too, and helps ensure the cake is baked throughout. It also has the advantage of giving you the option of cooling the cake upside down, which helps avoid the minor sinking and wrinkling that I have found inevitable when cooling the cake in a springform pan in the usual upright way.

Baking times and temperatures: The original recipe calls for higher oven temperatures – 190C/375F for 20 minutes, reduced to 165C/325C for a further 20 minutes (plus 10 minutes more with the oven off). The revised recipe calls for lower temperatures of 175C/350F and 150F/300F for 20 minutes each (also with 10 minutes more with the oven off). Twenty minutes at the higher temperatures seem to risk browning the cake prematurely in my oven, but I’ve also found that 40 minutes at the lower settings aren’t enough. I therefore compromise with starting at 190C/375F for 10 minutes, and then turn it down to 165C/325F for 40 minutes, giving it a total of 50 minutes with the oven on (instead of just 40). I make one quick rotation of the cake pan after 25 minutes (not sooner, to avoid a rush of cooler air deflating it before the cake has had time to develop some stability). I test it once it’s had the total of 50 minutes in the heat, before giving it a final 10 minutes under its paper hat with the oven off.

The most important thing is to know your oven and keep an eye on the cake; you can cover the top with a circle of buttered parchment at any point if it looks like it’s browning too fast, and bake it longer than specified if it needs it. Whatever temperatures you decide to use, do allow for a final 10 minutes with the oven off, even if you need to keep the jar slightly open. Don’t be tempted to skip this step as a sudden drop in temperature can cause more shrinkage.

Mixing order and ingredients: The original recipe folds the flour into the frothy egg yolks and sugar before the Sauternes and olive oil are added. This makes a tighter mixture initially than the revised recipe’s method of folding the flour in only after the olive oil and wine are added. I do the latter, as it seems to require a little less work to incorporate the flour; the more you have to mix, the more the gluten in the flour is activated, which contributes to wrinkly shrinkage on cooling.

The revised recipe uses less salt, and I do, too (¼ level teaspoon instead of ½ level teaspoon).

I get a lighter cake when using a fine ’00’ pastry flour (or cake flour as available in the States). You can duplicate this by substituting 2 tablespoons of plain (or all-purpose flour) with the same amount of cornflour (cornstarch).

The revised recipe uses less olive oil: 110 ml, or 1/3 cup plus 2 tablespoon; the original uses 150ml or 1/2 cup plus 2 tablespoons. Less oil makes the cake lighter.

The revised recipe splits the sugar into two halves: one to ribbon the egg yolks and one to help stabilise the beaten whites. This gives added strength and volume to the whites, so I do this, too.

The revised method also adds cream of tartar to the whites to help with the volume, but I find this unnecessary. The crumb texture is a little coarser with it, and I imagine that I can also taste it (which may be fanciful on my part). Don’t hesitate to use it, however, if you feel you’d like some help with the cake’s stability.

We are delighted to have adopted an olive tree at Fabio and Annarella’s farm, Zisolhouse, near Noto in Sicily, and thank them for making available to us the beautiful organic olive oil that goes into this cake (and into and onto so many other things in our English kitchen).

Other Sicilian recipes and stories on Crumbs on the Table:

- Sicily, part I: Noto town and markets

- Sicily, part II: Caponata

- Sicilian fast food: lemon spaghetti

- Sicilian vanilla gelato

Other citrus recipes on Crumbs on the Table:

Tour D’Argent: a remembrance of things past at today’s prices

Tour D’Argent: a remembrance of things past at today’s prices Apricots, les abricots

Apricots, les abricots I used to cook in a piggery

I used to cook in a piggery

Seed cake and story

Seed cake and story

Easter is late this year

Easter is late this year

Leave a Reply