This is one of the recipes I make most from my time cooking at Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, back in the ’eighties. It’s been one of my favourite things to eat and make ever since. This beautiful tart always surprises, always delights. Silky sautéed leeks, salty creamy goat cheese, and crisp buttery puff-pastry (I give a recipe here for making puff pastry from scratch, though you don’t have to): all the elements are just right for each other. It’s a masterly composition.

This is one of the recipes I make most from my time cooking at Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, back in the ’eighties. It’s been one of my favourite things to eat and make ever since. This beautiful tart always surprises, always delights. Silky sautéed leeks, salty creamy goat cheese, and crisp buttery puff-pastry (I give a recipe here for making puff pastry from scratch, though you don’t have to): all the elements are just right for each other. It’s a masterly composition.

Skip to recipes It’s one of many gems to be found in the Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook, published in 1982. My precious first edition is dog-eared, stained and scribbled on, and far more valuable to me for all that wear and tear. Leafing through it is like turning the pages of an old photo album and remembering some of the best times I’ve had with people around a table. Every time I’ve made this tart it’s been an occasion, not just a meal, inspiring rapturous amazement at what the humble leek is capable of. This tart defamiliarizes something we think we know, and makes us appreciate it anew.

When The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook was first published, it served as a quiet manifesto of what came to be recognised as the American food revolution. It was a seductive call-to-action that brought poetry to the back-to-the-land ideals of the times. It made vivid the links between environment, culture, food and politics because it was about paying attention to ingredients: how they are produced, as much as how they are prepared. It was a search for connections that had been lost, a way of valuing the interdependence of nature and culture; of respecting the land that nourishes people, and the people who work the land.

When The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook was first published, it served as a quiet manifesto of what came to be recognised as the American food revolution. It was a seductive call-to-action that brought poetry to the back-to-the-land ideals of the times. It made vivid the links between environment, culture, food and politics because it was about paying attention to ingredients: how they are produced, as much as how they are prepared. It was a search for connections that had been lost, a way of valuing the interdependence of nature and culture; of respecting the land that nourishes people, and the people who work the land.

This philosophy was joyous and sensual in a way that brought creative energy and optimism to the politics of rejection and protest. (We needed both then, and still do.) Above all, the ideas they were serving at Chez Panisse caught on because the food tasted so good. It wasn’t an abstract philosophy, it was real: food produced with care and treated with respect in the kitchen could blow your mind.

This book shaped my culinary aesthetics at a formative time when I was seeking a better way to live, cook and eat. I read Alice Waters’s introduction and recipes over and over, and her voice spoke to me like a kindred spirit. I had had my own epiphany in Europe as a student a few years before, and her descriptions of the revelatory food she had encountered there helped give me a language to understand why my own food discoveries had meant so much that I wanted to shape my life around them.

This book shaped my culinary aesthetics at a formative time when I was seeking a better way to live, cook and eat. I read Alice Waters’s introduction and recipes over and over, and her voice spoke to me like a kindred spirit. I had had my own epiphany in Europe as a student a few years before, and her descriptions of the revelatory food she had encountered there helped give me a language to understand why my own food discoveries had meant so much that I wanted to shape my life around them.

It was the natural simplicity, and what Waters called the “immediacy” of the food she described, that excited me — the tart made with raspberries from the garden, the trout fresh from the stream, the mixed small lettuces picked fresh each morning. This, I realised, was what had inspired so much joy throughout my own life: the wonder of things that grow, and the beauty of place; the taking into oneself all this charm through the act of making things; and the delight in sharing them with other people. Making beautiful food was a way of making life more beautiful, more harmonious.

For me, this recipe for leek and goat cheese tart captures a moment of shift in American food culture that, for all its romanticism, sparked something genuine and important, when we started to re-learn the importance of these connections, and to appreciate the innate beauty of ingredients (and explore ones new to us), awake to the superior flavour and value they have when treated with respect for the entire context in which they are produced.

I was blessed growing up to live in the countryside surrounded by fields, orchards and roadside stands, and to have gardeners in the family growing all kinds of beautiful vegetables and fruits. Yet leeks weren’t much known in the States at the time, and I had never tasted or even seen one before encountering them while a back-packing student in France in the 1970s, where they were a valued kitchen staple. To me leeks seemed an exotic, astonishing vegetable, with their crisscrossing dark-green leaves and long, white stalks (technically not stalks at all, but an accumulation of leaf layers that form a tight cylinder as the plant grows, the edible base of which is blanched white under the soil).

I was blessed growing up to live in the countryside surrounded by fields, orchards and roadside stands, and to have gardeners in the family growing all kinds of beautiful vegetables and fruits. Yet leeks weren’t much known in the States at the time, and I had never tasted or even seen one before encountering them while a back-packing student in France in the 1970s, where they were a valued kitchen staple. To me leeks seemed an exotic, astonishing vegetable, with their crisscrossing dark-green leaves and long, white stalks (technically not stalks at all, but an accumulation of leaf layers that form a tight cylinder as the plant grows, the edible base of which is blanched white under the soil).

I marvelled at them in the Parisian markets, strappy leaves and roots still attached, some so tall they were carried home on people’s shoulders like baguettes. I remember the first time I was served them trimmed down to their tenderest and poached whole, served in vinaigrette as a first course worthy of being eaten on their own. They represented a whole new culture, and wonder, and the kind of food I’ve come to love most: earthy, seemingly ordinary, yet extraordinary: capable with the application of knowledge and ingenuity of being transformed into something sublime.

I marvelled at them in the Parisian markets, strappy leaves and roots still attached, some so tall they were carried home on people’s shoulders like baguettes. I remember the first time I was served them trimmed down to their tenderest and poached whole, served in vinaigrette as a first course worthy of being eaten on their own. They represented a whole new culture, and wonder, and the kind of food I’ve come to love most: earthy, seemingly ordinary, yet extraordinary: capable with the application of knowledge and ingenuity of being transformed into something sublime.

This tart is indeed sublime. It’s a delicious way to do something spectacular with this versatile, indeed indispensable, vegetable. Leeks are an essential ingredient in many dishes, and of course a wonderful side-dish in their own right, but this gloriously golden centrepiece tart is the best way I know to feature leeks as the star of the show: either as a main course for lunch or dinner, or an elegant starter. It’s stunning, however you choose to feature it.

This tart is indeed sublime. It’s a delicious way to do something spectacular with this versatile, indeed indispensable, vegetable. Leeks are an essential ingredient in many dishes, and of course a wonderful side-dish in their own right, but this gloriously golden centrepiece tart is the best way I know to feature leeks as the star of the show: either as a main course for lunch or dinner, or an elegant starter. It’s stunning, however you choose to feature it.

More about leeks

Taste and texture

Leeks can do jobs no other member of the allium family can. They’re less dominating than onions, shallots or spring onions/scallions, without the heat or raw onion harshness that comes from these vegetables’ higher levels of sulphur compounds (though older, larger leeks will be stronger than leeks with slender stalks). Leeks have a distinctive flavour: mild yet complex, deeply vegetal, grassy and green, with a fresh, herbal sweetness. When cooked they are less purely sweet than cooked onions, and still freshly herbaceous, so substituting onions for leeks in any recipe will give an entirely different result.

Because the leek’s flavour profile covers a range of notes, it blends exceptionally well with other ingredients. Their delicacy makes them especially compatible with fish, scallops, poultry, and rabbit, though they are also lovely with lamb or pork (and even beef, especially if braised in stock). They are wonderful featured in risottos and pasta dishes, and braised with other spring vegetables like asparagus, peas and lettuce.

They can be dressed up with cream for sauces or gratins, or simple leeks on toast, an old English savoury that sadly isn’t often seen anymore. Leeks marry well with many herbs, from parsley, to sage, and thyme. My absolute favourite way to serve them as a vegetable side-dish is gently sautéed with butter and fresh tarragon.

Leeks are extremely useful as an aromatic in soups, stews, broths and casseroles (like onion, carrot, parsley, celery, etc…), where they add a depth of flavour that would be missing without them. I would never make a pot of stock without leeks, so always freeze the trimmings to have on hand for just this purpose.

They can be steamed, grilled, sautéed, boiled or braised; and chopped, sliced crossways, julienned (the choice for this leek and goat cheese tart), or trimmed down to their white stalks to cook whole. It’s also fashionable to fry shaved leeks for a crispy nest-like garnish.

Their texture, too, is distinctive, with a seductive mouthfeel. They’re not difficult to cook, but do warrant attention as they contain less moisture than onions and can catch on a hot pan more readily; and their slightly mucilaginous quality, which adds so much body to a broth and contributes to the silkiness that is one of their greatest virtues, can turn them rather slimy if they’re cooked to death, especially when boiled, steamed or braised.

They tend to retain heat longer than most veg, especially when cooked whole, so take this ‘repose time’ into account and stop when they’re still a little underdone, or plunge them into cold water to stop the cooking if you plan to serve them whole, for example, as leeks vinaigrette (drain them well after cooking with liquids as they can otherwise become watery). Anyone who thinks they don’t like leeks has probably encountered them overcooked, or had the misfortune to be served larger, woody leeks and/or the tougher outer skins.

The tenderest leeks are about 3-4 cm (up to about 1½ inches) in diameter, and these are the best to use for this leek and goat cheese tart, and most other leek recipes as they have the best flavour and texture. Thicker leeks are good, too, but will be stronger and are likely to require more trimming of the tougher, outer layers. Really thick ones are best in stews and soups. Baby leeks no thicker than a finger tend to be the most delicate and tender, and make an elegant presentation when grilled or boiled whole like asparagus; but smaller mature leeks are generally the better value, and more flavourful. Some varieties are bred to have longer white parts than others, but this also depends on how they are grown. The best leeks are blanched carefully over their long growing season by earthing them up gradually as they grow. This is why leeks have a reputation for being gritty, as soil can collect in between the developing leaves. They do have to be washed carefully, but I usually find that this is not a great issue, unless you’re lucky enough to have freshly harvested leeks at your disposal with roots and long leaves still intact. I think it’s no more trouble to deal with a leek than an onion, and there are fewer tears.

The first step is to cut off any loose dark-green leaves a few inches above the paler green and white part of the leek. The dark leaves don’t have much flavour and can be discarded, though if any feel pliable, you can clean them for the stock pot. Next, cut off the roots to cleanly reveal the rings at the base, with as little wastage as possible. With your fingers, peel off the weathered outer layer of the white and pale green parts of the leek, as it will also be too fibrous to eat. You may have to peel off more than one white outer layer if they are tough. You’ll know by testing with a sharp knife; if you encounter resistance, take off another layer until the knife goes through easily. Don’t waste the valuable trimmings; wash and freeze them for the stock pot. After trimming, give the leeks a good first rinse under running water to remove any obvious grit. At this point chop, slice, julienne or otherwise prepare the leeks for cooking, being watchful for any tougher parts that need further trimming. If cooking the leeks whole, cut down their length to within 5cm (2 inches) of the base; rotate and make a second cut the same length as the first, and then fan out the tops like a paintbrush, to clean them. Finish washing the cut leeks by filling the sink with plenty of cool water. Swish them around and inspect carefully. Repeat with fresh water until no more sand or grit is visible. Drain in a colander.

A brief history of the leek

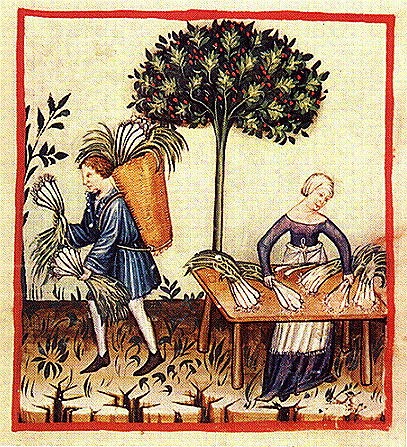

The cultivation of leeks from their wild botanical ancestors originated in ancient Egypt. The ancient Greeks brought them to France, and something like a modern leek was an important crop there in the Middle Ages. Several recipes using leeks appear in the country’s first cookbook, La Cuisiniere François (The French Chef), published for other chefs by chef François Pierre de La Varenne, in 1651. Leeks were also in common use around this time in Britain.

“Culture de poireaux au Moyen-Âge”: the medieval cultivation of French leeks. In France, the most highly-rated are from Créances, in Normandy, where monks have cultivated vegetables since the 11thcentury in sandy soils mulched with seaweed.

“Culture de poireaux au Moyen-Âge”: the medieval cultivation of French leeks. In France, the most highly-rated are from Créances, in Normandy, where monks have cultivated vegetables since the 11thcentury in sandy soils mulched with seaweed.

They were brought to Britain by the Romans, who considered them a “superior vegetable, unlike onions and garlic which were despised as coarse foods for the poor” (Nero was such a fan he was nicknamed the “leek eater”)[i]. For centuries, though, leeks were food for the poor across Europe, valuable in part because they were hardy enough to winter over and still provide something fresh and green when winter’s stores were bare and spring hadn’t yet gotten going. Leeks went into what Jane Grigson calls the “survival stews” that kept Europe’s peasantry alive, especially during March’s cruel hungry gap, when more people starved than in the depths of winter.

Ampler versions of these dishes are still highly regarded in many cultures, from the French pot-au-feu with boiled meats, and potage bonne femme (good old leek and potato soup); to the French-American cold vichyssoise; the Welsh mutton broth, cawl; and what Grigson calls the ‘soup above soups’, Scotland’s cockie-leekie, or cock-a-leekie (though “anyone”, she admits, “who knows it only from a tin may find that hard to believe”). All of these simple soups and stews she “swears are not easily surpassed.” [ii]

Leeks of course have a special status in Wales, as the national symbol. The practice of wearing and eating a leek on March 1st, St David’s Day (the day honouring the patron saint of Wales), persists to this day as (quoting Shakepeare’s Fluellen) a “badge of honourable service”, linked in legend to the 7th century battle against invading Saxons. Welsh warriors are said to have been led to victory in a leek field wearing a leek in their helmets so they could recognise each other in the melee (those leeks must have been more like the smaller wild leek than one we would recognise today). Shakespeare exploits the symbolism of leeks in his battle of Agincourt history play, Henry V, for both comic and poignant effect [iii], reminding his audience that the medieval warrior king who called his men to arms for “Harry, England, and St George”, was born a Welshman.

In the North East of England there is a tradition of competitive leek-growing, where local “Leek Clubs” provided a social outlet for working-class men, in particular, especially in colliery villages and towns. As well as helping to feed their families from the fruits of their allotments, the most dedicated giant veg enthusiasts could win accolades and significant cash prizes for the longest and heaviest leeks at local and regional annual shows (the 1987 winner’s entry was over 5 kilos). Competitions were judged against serious standards, and the sometimes excessive lengths to which growers would go to win (e.g., floodlighting and all-night vigils to fend off thieves) was the subject of much humour and good-natured rivalry, including gender-rivalry. Women took on the men in some areas with their own clubs, e.g., the Boldon Colliery Ladies’ Leek Club in Northumberland; and the Ladies’ Leek Club in Knottingley, Yorkshire, where prize-winner, Mary Riley, shown in the charming photo below, sang to her leeks to help them grow.

Mary Riley singing to her prize-winning leeks, 1984. Photo reproduced by kind permission of Mirrorpix.com.

Mary Riley singing to her prize-winning leeks, 1984. Photo reproduced by kind permission of Mirrorpix.com.

During its long history, the leek’s status has run the gamut from poor man’s food, to favourite of emperors and kings, to symbol of a nation, and working-class resilience. Its current status in the British and American home-kitchen is on the up as we become ever more conscious of the value of vegetables in our diet. Our treatment of leeks is becoming more adventurous, too, as we look back to old classics and to different cultures for culinary inspiration, including Middle Eastern cookery where leeks are also widely used, often with interesting ingredients such as sumac, yogurt, preserved lemon, and mint. The best restaurants in this country have been celebrating the leek in style for some years, as they always have been in French kitchens, home and professional.

Known still in France as ‘poor man’s asparagus’ (asperge du pauvre), leeks are much cheaper there than they are here, and feature in many dishes both humble and grand, from elaborate constructions with truffle, to classic leeks vinaigrette, and leek tarts similar to this one from Chez Panisse. I have to say I’ve paid more for leeks by the kilo here in England than I have for asparagus, but I still think they are one of the most valuable vegetables in any cook’s repertoire, with a flavour all their own and hard to beat. Making them a centrepiece of a meal with this beautiful tart is excellent value.

This tart is worth the leeks. And the goat cheese, and the puff pastry. If you’re going to do one amazing thing with leeks this season, I really don’t think you’ll regret choosing this.

FOOTNOTES

[i] Tom Jaine, editor: The Oxford Companion to Food, third edition (2014). Oxford University Press; p. 461.

[ii] Jane Grigson, Good Things. Penguin, 1973; pp. 190-197.

[iii] William Shakespeare, Henry V; Act IV, scene vii. The Welsh Captain, Fluellen, reminds the king: “If your Majesties is remeb’red of it, the Welshmen did good service in a garden where leeks did grow, wearing leeks in their Mommoth caps; which your Majesty know, to this hour is an honourable badge of service; and I do believe your Majesty takes no scorn to wear the leek upon Saint Tavy’s Day”. To which the king replies, “I wear it for a memorable honour; For I am Welsh you know, good countryman.” Act IV, scene I. The Englishman, Pistol, makes the mistake of insulting Fluellen: “I’ll knock his leek about his pate Upon Saint Davy’s Day.” In retribution, Fluellen forces him to eat it: “If you can mock a look, you can eat a leek”.

I. Chez Panisse leek and goat cheese tart

Makes one 23cm (9-inch tart), serving 6 (or up to 8 as a starter)

Adapted from The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook, by Alice Waters (1982)

This tart is made with a generous quantity of cooked leeks and just enough rich custard to bind them: it’s not a custardy quiche. It’s baked on a puff pastry base shaped free-form directly onto the baking sheet, not in a tart-tin, which makes it easier to get the really crisp and flaky bottom crust that adds so much to the texture. You will still need a 23-cm (9-inch) tart ring with a removeable bottom. The outer-ring turned upside-down on top of the pastry helps the tart keep its shape while baking.

Homemade puff pastry (recipe below) elevates this tart to the extraordinary if you have time and inclination, but a bought puff pastry will still be delicious – just make sure you use one that’s made with all butter.

There is a tradition in France and Belgium for cooking leeks into flans and tarts, mostly made with shortcrust pastry. Jane Grigson gives a recipe in her Vegetable book for a Cornish leek pie that has a puff pastry top (only), and a Welsh version with both a bottom and top crust. Most of these traditional tarts also include bacon, as does the original Chez Panisse recipe I’ve adapted here.

Pancetta or bacon are certainly delicious in this tart, too, but I prefer it without, and save the lardons for the Alsatian onion tarte flambé I make from Madeleine Kamman’s recipe. It’s purely personal preference, but for me, the meatless version highlights the freshness of the leeks. But add it if you wish. There is plenty of precedence for doing so.

The leeks really are the star, so choose ones that are as fresh and flavourful as you can find, and ideally no more than 3-4cm (1½ inches) in diameter. This amount of prepared leeks looks like a lot, but they will cook down dramatically. You will need a large pan to take them all.

*How much to buy?

Because leeks vary greatly in how much dark green leaf and root is left on when they are sold, I’ve given the precise weight for prepared leeks you will need — i.e., the edible portions only that will go into the tart. You will need 500g, or just over one pound.

- As a rule of thumb for leeks sold untrimmed, you may need to buy between two and three times as much in weight as you need in prepared leeks (i.e., 1.25 to 1.5 kilos to yield 500g edible leeks).

- For tender leeks that are trimmed down to the straight stalk with little dark green attached, you may need to buy just about twice the weight as you need, to allow for wastage (i.e., 1 kilo to yield 500g).

- If your leeks are thicker than 3-4cm (1½ inches) in diameter, allow extra for trimming off more of the outer layers, in case they are tough.

**How to julienne leeks

Slicing leeks into matchstick-sized strips, or julienne, is a good way to prepare them for this tart as they make for manageable mouthfuls that are easy to cut through.

- Start with leeks that have been rinsed and trimmed down to just their tender white and pale-green parts, with any dark-green leaves, roots and tough outer-layers removed.

- Holding each trimmed leek stable on a cutting board, use a sharp knife to cut through it lengthways into two equal halves.

- Laying each half cut-side-down so they are stable on a cutting surface, cut through each half into thin, long strips, about 1/8 of an inch wide.

- Cut these longer strips into shorter match-stick-sized pieces, about 5cm (2 inches) long. Rinse well and then drain well before cooking.

- One-third of the recipe for puff pastry, below; or enough ready-made all-butter puff pastry to roll a 26-27cm (10.5 inch) circle

- 500g (1 pound 2 ounces) julienned leeks, washed and drained; see notes above for how much to buy* and how to cut them for this recipe**

- 115g (8 tablespoons, or 4 ounces/1 stick) unsalted butter, divided into 85g (3 ounces) and 30g (1 ounce)

- Optional: 115g (4 ounces) pancetta or bacon, thinly sliced and cut into 1.25cm (½ inch) pieces

- 1 large egg

- 120g (½ cup) double (heavy) cream

- 2 level teaspoons smooth Dijon mustard

- 1/8 teaspoon mild curry powder

- 115g (4 ounces) creamy-textured goat cheese without rind — crumbled (not too finely)

- 1/3 cup fresh white bread crumbs

Directions

Tip: You can start shaping the tart shell once the leeks are cooking. Alternatively, shape the tart shell in advance and keep it chilled. You can also cook the filling in advance and keep it chilled until ready to bake. Fill the pastry shell just before baking so it doesn’t get too wet.

-

- Cook the leeks: In a large open sauteuse or frying pan, sauté the julienned leeks over medium-low heat in 85g (3 ounces/6 tablespoons) of the butter, stirring frequently, until they are almost soft, about 20 minutes. Make sure they don’t brown at all. Cover the pan and turn the heat to low; let the leeks sweat for another 10 minutes until they are silky soft, but not falling apart or mushy. Salt and pepper them to taste. Set aside to cool for about 10-15 minutes.

- If using the pancetta or bacon, cook it in a separate pan for about 10 minutes or until it has rendered its fat and any water, and drain it on kitchen paper.

- Make the custard: Mix together the egg, cream, mustard and curry powder in a small bowl with a fork until smooth. Add half the goat cheese, and stir it through gently. Set aside.

- When the leeks are just barely warm, add the custard (and pancetta or bacon, if using), and mix well with a spoon, breaking up any clumps of leek so everything is well combined. (You can prepare the leek custard to this stage and keep it chilled overnight, if you wish, before filling the tart next day).

- Shape the pastry shell (Do this while the leeks are cooking, or the day ahead if you want to for convenience, and keep it chilled):

- Roll the pastry into a circle 26-27cm (10.5 inches) in diameter and 1/8 of an inch thick.

- Using the removeable base of a 23cm (9-inch) tart ring as a guide, cut the circle 2.5cm (1 inch) bigger than the metal base, to allow for the sides of the tart. You should end up cutting a flat circle of pastry 25.5cm (10-inch) in diameter.

- Transfer the pastry circle onto a parchment-paper- or silicone-lined baking sheet. Chill it on the baking sheet for half an hour to rest the dough and make it easier to roll up the sides.

- Once chilled enough to handle easily, shape a free-standing tart shell by rolling up the sides of the pastry to a depth of 2.5cm (1-inch). Take the outer ring of the tart-ring, freed from its metal base, and holding it upside down, place it carefully on top of the pastry shell to help contain the sides and keep the shell in a neat circular shape. Refrigerate the shell for another 30 minutes on the baking sheet; this resting period minimises any shrinkage of the pastry and helps with flakiness and tenderness. You can cover it and leave to chill overnight if you wish.

- Fill the pastry shell: When ready to proceed with baking the tart, spoon the cooled leek custard mixture into the chilled pastry shell and spread it evenly right to the edges. Distribute the rest of the crumbled goat cheese over the filling; then scatter the fresh bread crumbs over the top. Melt the remaining 30g (2 tablespoons) of the butter and drizzle it over the breadcrumbs as evenly as possible.

- Bake the tart:

- Heat the oven to 200C/400F. Bake the filled tart for an initial 15 minutes. Check that the sides of the tart have puffed and set under the metal ring. If so, carefully remove the metal ring from the top of the tart (if not, give it another 5 minutes).

- Reduce the oven temperature to 175C/350F, and bake the tart for a further 30-40 minutes, or until the pastry is puffed and flaky and golden on top with some golden-brown accents; and crisply golden brown underneath. You can test the bottom by carefully lifting up a corner of the tart with a spatula. It should be browned all the way to the centre.

- Heat the oven to 200C/400F. Bake the filled tart for an initial 15 minutes. Check that the sides of the tart have puffed and set under the metal ring. If so, carefully remove the metal ring from the top of the tart (if not, give it another 5 minutes).

- Serve right away, or move the tart to a cooling rack to keep the bottom from getting soggy.

- Cook the leeks: In a large open sauteuse or frying pan, sauté the julienned leeks over medium-low heat in 85g (3 ounces/6 tablespoons) of the butter, stirring frequently, until they are almost soft, about 20 minutes. Make sure they don’t brown at all. Cover the pan and turn the heat to low; let the leeks sweat for another 10 minutes until they are silky soft, but not falling apart or mushy. Salt and pepper them to taste. Set aside to cool for about 10-15 minutes.

Adapted from Dan Lepard, Short and Sweet: the Best of Home Baking; and Alice Waters, The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook

Making puff pastry is fun! It’s not difficult, but it does require time. You need to allow about six hours, as it needs time to rest in the fridge in between the short bursts of rolling and folding that are required to give it the multiple layers that makes it so light and flaky. The flavour and texture are worth it. It’s a rewarding job for a day when you’re around the house and can stop every so often to spend ten minutes tending to a kitchen project. Or you can spread it out over two days if that’s more convenient.

If you do spread it out over a couple of days, you will need to let the deep-chilled dough sit at room temperature for some minutes until it’s pliable enough to roll without the butter cracking. And likewise, if at any time you find the dough too soft to handle easily, stop and give it a spell in the fridge.

This recipe makes more than you need for this one tart, but it is easier to make in larger amounts, and great to have the rest on hand in the freezer. It’s a versatile classic pastry that can be used for either sweet or savoury dishes.

There are of course various ways of making puff pastry. My preferred way these days combines the methods of Dan Lepard with that given by Alice Waters in the original Chez Panisse recipe for the leek and goat cheese tart.

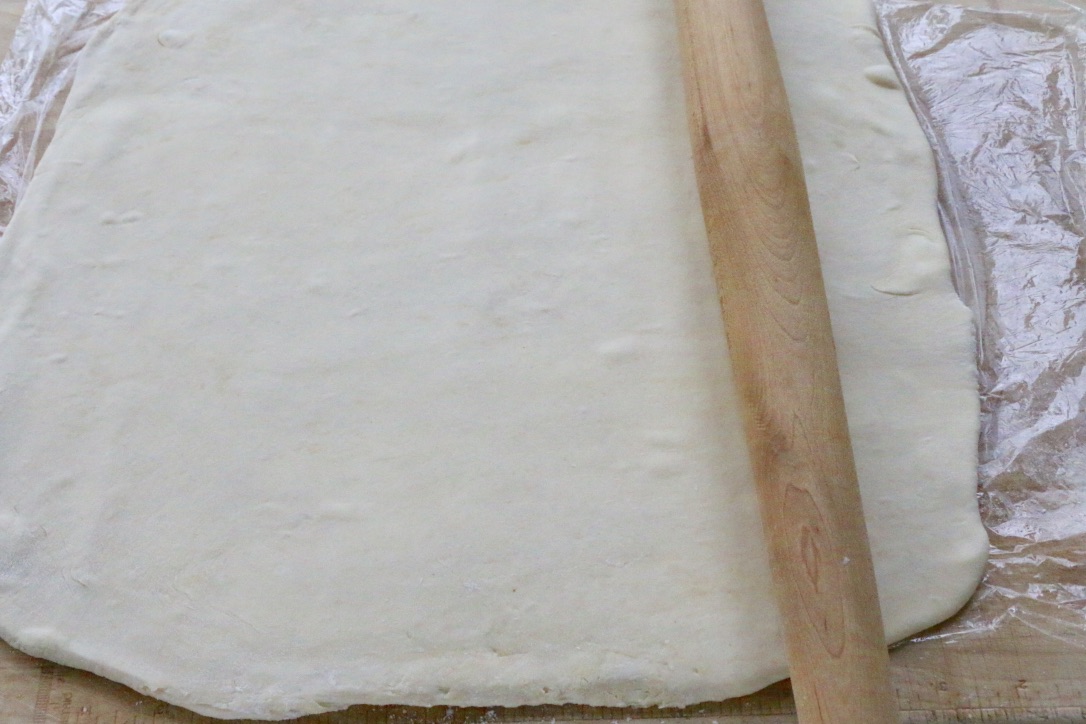

Puff pastry is made by layering a basic dough with a generous quantity of butter, and then folding and rolling it in a sequence of steps called “turns” to build up an impressive 730 micro-layers of butter alternating with pastry. The moisture in the butter layer produces steam when it hits the the heat of the oven, and this makes the layers of pastry rise. After making the initial dough to accept the butter layer, you then make a total of six “turns”, resting the dough in the fridge between most of the turns.

I suggest you read the instructions through before you start. It looks daunting, but once you get in the swing, it all becomes clear.

Ingredients

- 450g (1 pound) all-purpose (plain) flour

- 1½ level teaspoons cooking salt

- 1 tablespoon strained fresh lemon juice

- 240ml (1 cup) cold water

- 565g (1 pound 4 ounces) total unsalted butter, divided into 115g and 450g (4 ounces and 1 pound)

Directions

- Before you start, set the butter out at room temperature to soften slightly. It should be malleable, but still cool (not as soft as for making a cake or cookies, and not at all greasy).

- Make the initial dough: In a large bowl, sift together the flour and salt. Using the tips of your fingers, rub 115g (4 ounces) of the slightly softened butter into the dry ingredients until they are well worked in (no visible bits of butter should remain).

- Combine the lemon juice and cold water, and gradually work the liquids into the flour/butter mixture in the bowl, using a fork to combine them just until everything comes together into a rough ball. If it continues to crumble, add a very little more water, but not too much. It should not be at all sticky. Give it a couple of gentle kneads to shape it into a disc, but don’t overwork the dough or it won’t readily accept the butter; it shouldn’t be smooth at this stage, just intact. Cover with cling film and refrigerate for 30-45 minutes to relax the gluten and make the dough easier to work.

- Apply the rest of the butter: Using a lightly floured rolling pin, roll the rested dough into a rectangle 45cm x 23cm (18 by 9 inches). Work on a pastry board or other work surface covered with overlapping cling film, or very lightly dusted with flour.

TIP: The less flour you use the better, so I prefer rolling onto cling film. The dough will become smoother as you roll it into shape. Try to keep the edges as straight as possible.

- You now want to cover two-thirds of the surface of the rectangle with an even layer of butter. Either slice or pinch the softened but still-cool butter into equal-sized pieces to lay evenly on top of the dough. Leave one-third of the rectangle free of butter.

TIP: The butter should feel roughly the same temperature and texture as the dough: cool and not at all greasy, but soft enough not to tear the dough. If the butter is too cold, it will crack upon rolling and tend to tear through the dough. This similarity in temperature and texture helps the layers of butter and dough to bond.

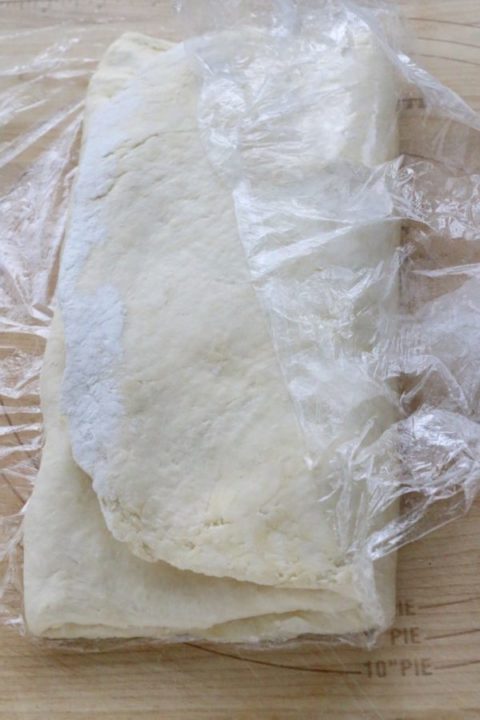

- Fold the unbuttered third of dough over half the buttered dough, leaving the other third of buttered dough exposed.

- Now cover the third of the buttered dough that’s still exposed in this fashion: give the double-layer one more fold, so it lands on top of the third of the rectangle covered in butter. Press the dough-package lightly with a rolling pin to get rid of any air bubbles and make it bond together.

You will now have a neat, long, narrow, package of dough folded into three layers like a letter ready to go into an envelope. It will contain two inner layers of butter separated by three thicker layers of dough. This is the start of the layering that makes the pastry so flaky.

You will now have a neat, long, narrow, package of dough folded into three layers like a letter ready to go into an envelope. It will contain two inner layers of butter separated by three thicker layers of dough. This is the start of the layering that makes the pastry so flaky.

Having introduced the butter into the dough, you are ready to commence the phase of rolling and “turning” that creates the accumulation of layers.

8. Make the first of six “turns”: Turn the dough 90 degrees so you can work in the opposite direction as you did the first time, and roll out a rectangle once more, the same size as before: 45cm x 23cm (18 inches by 9 inches. As before, fold the rectangle into a neat, long, narrow package of three overlapping layers. You’ve just completed the first “turn”. To help you keep track of the turns, make one notch in the dough using the blunt back of a knife. Wrap the dough in cling film and refrigerate it for 30-45 minutes.

9. Make the second turn: Roll in the opposite direction as last time to form the rectangle as before; and again, fold it into overlapping thirds. Notch the dough twice to indicate you’ve done two turns. Wrap and chill for 30-45 minutes.

TIP: If you find the butter layer is harder than the dough itself, let the dough sit at room temperature for a few minutes until it is soft enough to roll smoothly without tearing. Should you tear through the dough and expose any butter, use a little flour to cover up the flaw, and proceed as usual.

10. Make the third and fourth turns: Roll the chilled dough into a rectangle again, working in the opposite direction as you did the first time. As before, fold the rectangle into a neat, long, narrow package of three overlapping layers. Turn it 90 degrees and roll it again into a rectangle as you’ve been doing; and fold this rectangle into three overlapping layers in the usual way. Notch it four times to keep track of the number of turns so far. Wrap the dough package and chill it for an hour this time, as you made two turns.

11. Make the final two turns: To finish the puff pastry, follow the same sequence of rolling and folding two more times, for a total of six turns, so you end up with a silky, smooth dough folded into three layers as one long, narrow package of dough. Chill for at least one hour, or for up to a day, until ready to use. The photo below shows the amazing, multiple, mini-layers of the finished pastry, ready to cut into blocks to use or freeze.)

12. You will need one-third of the dough for the Chez Panisse leek and goat cheese tart. I suggest you cut the finished dough into three equal pieces, wrap each well, and freeze any you don’t plan to use within one day. Thaw frozen pastry overnight in the fridge if you can and let it sit at room temperature for a short while to make it easier to roll out for your recipe (or defrost at room temperature for 3-4 hours).

REFERENCES

- BBC blog on the folklore of the leek in Wales: http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/wales/entries/531cbdfa-be23-3bfa-b37e-446b779a94ec

- Jane Grigson, Good Things. (1973) Penguin, pp: 190-197.

- Jane Grigson’s Vegetable Book. (1978) Penguin, pp: 291-302.

- Tom Jaine, editor, The Oxford Companion to Food. Third edition (2014) Oxford University Press, p: 461.

- Dan Lepard, Short and Sweet: the Best of Home Baking. (2011) Fourth Estate; pp: 399-402.

- Marian Morash, The Victory Garden Cookbook. (1982) Alfred A. Knopf; pp: 154-161.

- Polly Russell, writing in the Financial Times Magazine, September 19, 2014. “The history cook: Le Cuisinier François, by La Varenne”. https://www.ft.com/content/a2a61b4c-3f84-11e4-a5f5-00144feabdc0

- François Pierre de La Varenne, La Cuisiniere François (The French Chef), 1651; translated by Terence Scully as part of La Varenne’s Cookery and reprinted by Prospect Books, 2006.

- Alice Waters, The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook (1982) Random House; pp 147-148.

- Bee Wilson, writing in the Telegraph, 27 Feb 2009. “Wearing leeks on St David’s Day”: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/4805288/Wearing-leeks-on-St-Davids-Day.html

- Photo: The photo of the whole tart being served by a woman in a blue dress was taken by O Restif, of Katherine R.

- Photo: Culture de poireaux au Moyen-Âge, by unknown master – book scan, Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5023605

- Photo: “Mary Riley with two prize winning leeks, 1984) reprinted with kind permission of Mirrormax.com. First published in the Chronicle Live, Newcastle, “Leek growing in the North East over the years”, By David Kenny 15 SEP 2014;15:47 (photographer unidentified). https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/lifestyle/nostalgia/gallery/leek-growing-north-east-over-7775171

Other Crumbs on the Table stories about vegetables, fruits and their history:

Other savoury tart recipes on Crumbs on the Table:

Tour D’Argent: a remembrance of things past at today’s prices

Tour D’Argent: a remembrance of things past at today’s prices Apricots, les abricots

Apricots, les abricots I used to cook in a piggery

I used to cook in a piggery

Seed cake and story

Seed cake and story

Easter is late this year

Easter is late this year

Leave a Reply